Table of Contents

Can’t Touch This

Warren Buffet was once asked why he owned a 5% stake in The Walt Disney Company. In his reply, Buffet drew a comparison between Mickey Mouse and the human actors that are on the payroll of most movie studios: “It is simple, the Mouse has no agent”.

Buffet reasoned that once you have created the first unit of an intangible asset, every unit after that costs next to nothing to produce. As you draw Mickey Mouse, you generate an infinitely scalable asset, a feature unshared by human actors. Thus, while other competitors in the entertainment industry had comparable revenues, their profits were thinner due to the costs associated with paying the cast, the agents, and directors.

Software is the same thing; it may be expensive to develop, but to multiply subsequent lines of code is a copy and paste process. If you were to sell computer hardware, on the other hand, every additional unit would require extra materials and labour.

The scalability feature of intangible assets, such as intellectual property and software, unlocks exponential growth and global reach because it allows organisations to escape the positive relationship between output and total cost of production.

Unfortunately, or luckily, we cannot softwarise everything. So how would you reach global presence in an industry that requires hardware to run operations, like transport or hospitality?

Here’s the pitch:

Because tangible assets are not quickly and cheaply scalable, I am not going to invest in them. My workers will.

Be Less the new More (For More we cannot afford)

The rise of the sharing economy can be attributed to the minimalist movement, and the rise of the minimalist movement can be attributed to millennials being broke.

Sharing economy firms have been successful in creating a better experience for the consumer: from an easier, faster booking experience to review systems that incentivise quality maximisation. Nevertheless, the success of these companies is largely due to more competitive pricing. But cost reduction hasn’t been achieved through the joint or alternating use of a resource that would be sitting idle or underexploited. Costs are merely transferred to the gig workers.

Take ride-sharing apps. These companies take roughly one-third of ride fares for providing a booking platform, while the driver has to shoulder the car purchase/lease, maintenance, gas, washes, insurance, social security expenses and labour risk — which, in times of COVID, is no small factor. As political economist Robert Reich puts it:

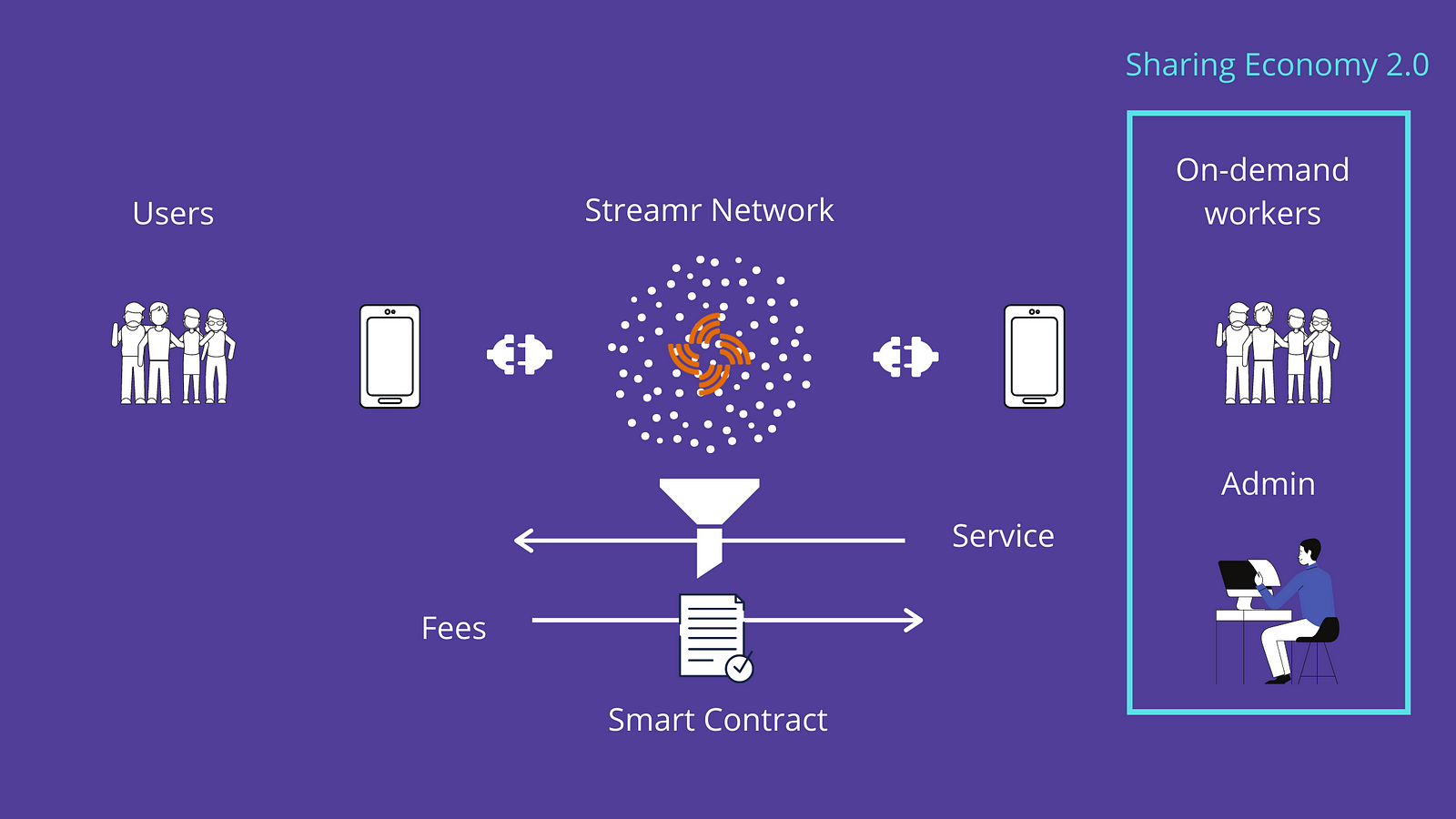

“The big money goes to the corporations that own the software. The scraps go to the on-demand workers.”

Make it ‘till you Fake it

Since software is very easy to scale, it is also to replicate. Intangible assets tend to create spillovers, and firms realised that to spear away competition they should become as big as possible as quickly as possible. While this strategy might work, coming up with a unit economics that holds true only in monopolistic conditions is not going to be labelled as savvy business management. But these are strange times, and investors are willing to keep unprofitable companies on life support high on a cocktail of loss aversion, excess capital and a perverted love for the founders.

As these firms reach the juggernaut status without any trace of profitability, the narrative keeps its pendulous motion between “We are good because we bring more wage-earning opportunities to more people” and “we expect to be profitable within one year” to maintain the pretence of a functioning business model. In this fabrication, the winners are the executives, with their obscene compensation that can be solely justified by fundamental attribution errors (FAE), and the investors who passed the ticking bomb to a greater fool. Unsurprisingly, the parties that are better off are the unproductives.

Tech, tech-enabled and tick-tacks

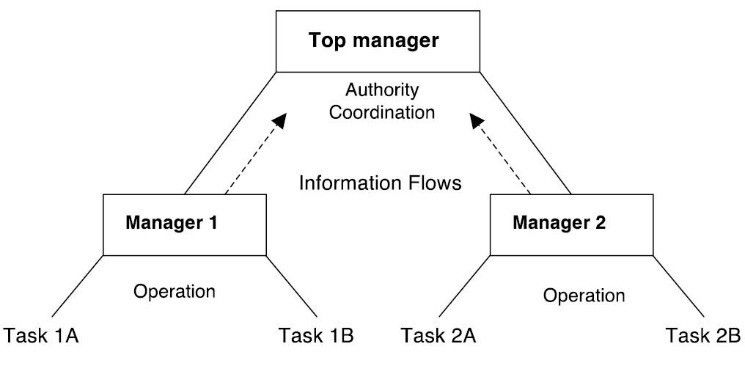

The sharing economy’s value proposition is nothing newfangled. A p2p network system that connects offer with demand is intuitively a good idea. In an analogue fashion, we have been doing that for the past 8000 years. Without much originality, the business model was executed through a U-form corporate structure, which implies central authority and coordination, as well as data processing.

The centralized structure provides an attractive benefit in enabling the fulfilment of the company’s vision through a clear chain of command. Innovation, for instance, is an exercise that requires some degree of centralization. In her book Quiet, Susan Cain argues that brainstorming with a large group of individuals tends to have a levelling effect on creativity because the initial goal of conceiving great ideas quickly turns into reaching a consensus among participants, thus diluting the quality of the concepts.

In other words, if you are in the business of doing things differently you shouldn’t give too much weight to the opinion of the crowd.

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” (Attributed to Henry Ford)

Sharing economy firms brought some change, but their type of innovation is more of a one-off. These firms are not in the business of continuous innovation in the way pure tech enterprises are. Still, they like to market themselves as such because on Wall Street “The new thing” never goes out of fashion ( adding a premium to a stock price is, sometimes, as easy as adding “Technologies” or “Blockchain” to the name of the organisation ). Yet under the surface, these firms are tech-enabled service companies. At the core, they are exchange systems. And exchange systems work better without a central processing unit.

While distributing creativity is a bad idea, distributing big data processing is a good one. Because the selection of experts or expert committees happens in a deterministic manner, their analysis may be more subject to political forces and other biases. Further, the greater headcount gives crowds a unique advantage when it comes to finding equilibrium points.

History has plenty of examples of data processing gone wrong because of centralization. To take a relatively recent one: when bread prices are set by a nepotistically selected group of government officials, people line up for the crumbs. When market forces are free to set prices, bread lines up for people.

The Network

To the on-demand worker, software in the sharing economy equals the latifundia in Medieval Europe: access to it is subject to the reverence of the holy software-owner and the acceptance to have no voice and little to no rights.

A fairer system may be a leaner system, scrubbed from the old business mould. Regrettably, in the early twenty-first century, the corporate apparatus comes with the software just like the medieval landowner comes with the field. While the development of the end-user application can be left to anyone as long as the right incentives are in place, engineering a global back-end infrastructure for data transfer is a way more complex task.

To substitute an enterprise messaging system you would need a universal, secure, robust, neutral, accessible and permissionless real-time data network. This should provide on-demand scalability and minimal up-front investment. There should be no vendor lock-in, no proprietary code and no need to trust a third party with the data flowing through the network. This system should also integrate smart contracts, which are self-executing and have the terms of the agreement written into lines of code. Taking again the example of ride-sharing: GPS data points may funnel down to the smart contract to assess whether the ride has been completed according to the path set forth when the service was booked, thus releasing the ride fees to the driver only if the contractual obligations are met.

If you think this is a lot to ask, the Streamr Network ticks all the boxes.

It should be said that the Network’s full decentralization will be achieved in the next stage of development. Nevertheless, as of today, it is up and running like a charm.

2.0

The new organisation requires pioneering rules to be coded in. Among the many: the logic by which the smart contract rewards the operators, how ownership is distributed and diluted, which assets claim ownership and how governance takes place. These questions have no right answer and require some rational extravagance in exploring these uncharted territories. Research in the area, albeit limited, is growing steadily and is attracting an increasing number of professionals and devotees from all disciplines.

As regards exchange systems, the argument that a centralized solution is always better is a weak one. While the execution risk in decentralizing the sharing economy is quite high, decentralization is a much stronger proposition because on top of disintegrating agency costs it enables its working community to own the business as they earn their wages.

Asset ownership is key to the effort of reducing the inequality gap. The money printer will not stop going Brrr and the currency in your pocket is still just colourised paper. What this means is that if your only source of income is your salary, then there is some probability that you will only get poorer.

If monetary economics is not your cup of tea, I invite you to check the chart of the S&P 500 or any Real Estate Index from 1971, then check the trend of real wages starting from the same period.

Wrapping Up

The new value models that are emerging from the convergence of the economic market system with information technology may terminate the traditional divide between the owners of capital and the workers. The Sharing Economy, essentially a collection of exchange systems, could be among the first to evolve from the old Industrial Value Model to a Distributed Value Model, where the right mix of technology and humanity can unleash greater economic potential.