During my time as a Guardian journalist, the then Readers’ Editor, Chris Elliott, told me a story. Not long after launching the paper’s website, in 1999, the office began receiving cheques. Loyal readers wanted to offer payment for what they’d read online, as they were doing with print just a few weeks before. The only issue was that these digital readers didn’t know where to send the cash.

It was an awkward moment. The pioneers of Web1.0 had told management that if they wanted to reach a mass online audience, content would have to be free. Internet users wouldn’t put up with the friction of online payments. If the Guardian wanted to monetise their efforts, they should look to advertisers, not readers, for funding. So the Guardian ended up sending the cheques back.

We now know how that “free content” strategy panned out for the media as a whole; dwindling income, monopolisation of advertising revenues by Facebook and Google, sacked journalists, reams of clickbait articles, attention grabbing fake news and the subversion of democracy. In the search for rapidly onboarding users, sustainable business models and incentives had failed to be designed properly and in the end the product, and the industry producing it, had ultimately been undermined.

I was reminded of this story whilst listening to internet pioneer Brewster Kahle at DevCon4 when he asked, “How do we get beyond the original sin of the web: advertising?”

The answer is of course much more realisable than it ever has been. Reader micropayment systems such as those being implemented by Brave, are finally offering media companies a real chance to readjust the interests at play between advertisers and readers. This is the promise of Web3.

And yet just as the media might be fixing a disastrous strategic error, the community of people tasked with creating the fix — dApp makers and Web3 UX designers — might be making the very same error themselves.

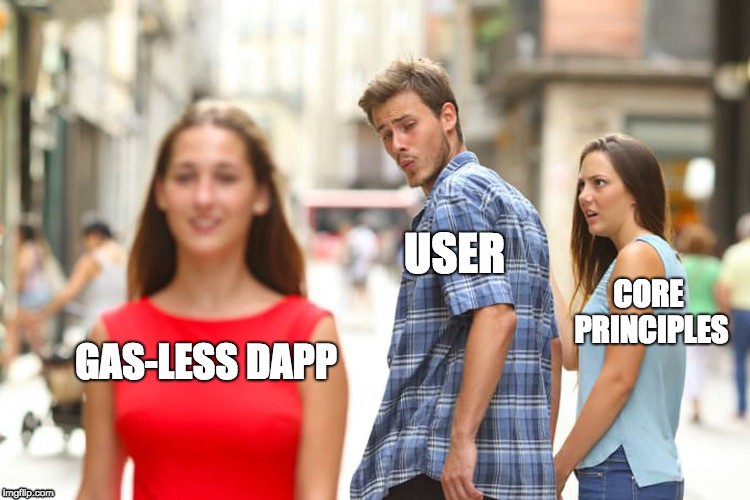

During DevCon4 the one thing that caught my ear, were the fairly recurrent conversations about whether to abandon gas costs to help dApps increase their user base.

When it comes to onboarding users, we can all agree, gas payments are a UX nightmare. Which designer would want users to face a lifetime of permissioning another window in Metamask and figuring out what the hell a gwei is, let alone how much gwei they need to result in an outcome that may (or may not) take place? Although these payments are vital to keep a number of decentralized networks going, they don’t really add anything positive to the user experience. They’re a necessary but very inconvenient hassle. Rather like road tolls. And the last thing crypto needs right now is more road tolls.

Ridding users of the hassle of gas costs is already happening. Peepeth, Crypto’s version of Twitter, has already enacted such a change. It was something Peepth’s Andrew B Coathup scoped out back in May. And according to Peepeth’s founder, they may go further with this.

Similarly worried about user onboarding, the ever brilliant Austin Thomas Griffith created a burner wallet to demonstrate gas-less wallet creation.

Introducing the 🔥👛 Burner Wallet 👛🔥 for “Ethereum in Emerging Economies – Mass adoption will start where decentralization is necessary” https://t.co/fvuHoZLhCh One phone sends DAI to another in seconds without any wallet download, seed phrase, or gas!! https://t.co/K26u8Bcw94

— Austin Griffith (@austingriffith) November 9, 2018

And yet, however much trying to eliminate gas as a part of Web3 interactions seems like a good idea, it strikes me (and I’m not a UX designer, just a crypto enthusiast approaching these problems from the economics side of things) killing gas payments for end users is a possibly disastrous move. If someone has to pay for gas costs on a decentralized network, and that someone isn’t the people using the service, then who will pay?

To start with, dApp buidlers might want to pony up for gas costs. At the launch of a product, these costs are likely to be a fairly insignificant in a project’s overall budget. But if dApp user numbers do take off, then projects paying for gas out of their own funds (especially if this means paying for Ethereum gas costs) won’t be sustainable for very long.

The real horror is that advertisers step into the gap — paying gas as a way of harvesting user attention and maintaining their Web2 business model for the Web3 era. And if it isn’t advertisers, then there are any number of other ways that a given network’s user base could be controlled through third parties offering to pay for user gas costs.

So if users aren’t habituated to paying for gas now, or the space finds sustainable gas free solutions that keep users firmly in control, then unwinding “look, no gas!” dApp designs five or ten years from now, may well prove impossible when interests and behaviors become entrenched. Like print media, we’ll all be rueing the day we made gas “free”.

So do we just persist with gas payments even though this might mean turning a good number of people off dApps altogether? Making this choice wouldn’t be too dissimilar to the UX decisions the space has made in regards to user security and privacy. Also at DevCon4, Taylor Monahan detailed MyCrypto’s brave decision to stop people entering their private keys directly on to the site in order to ensure user security even though doing that meant user numbers falling off a cliff.

But you stand by your principles right? Speaking to Laura Shin at the Oslo Freedom forum earlier this year Amber Baldet, founder and CEO of Clovyr, put it this way :

Historically there is generally a trade-off between security and privacy and convenience and … a sentiment that runs through the communities of people who care is that other people should just care enough to get over it [the inconvenience]. And if they understood the world the way that we do, then they would see the value in clicking this extra button or understanding these different settings.

So if we’ve created plenty of Web3 frictions in the name of privacy and security, why not create a few more to stop networks being captured by third party interests?

The inconvenience of gas costs could even be sold as a genuine plus point. Ethical consumerism is sorely lacking in the digital sphere and given that Web3 is already running on that pitch, gas could be marketed as the stand out feature which demonstrates how dApps really are different from apps. Paying gas sets you free.

If that strategy isn’t very persuasive, there might be another way forward. Instead of getting third parties to pay to make experiences more convenient for users, why not instead pay users to be inconvenienced?

Here’s an example.

Kickback, is crypto’s version of Eventbrite. To attend an event, you register with your Ethereum ID and reserve your place by sending a deposit in ETH (oh and paying the required Ethereum Network gas costs to process the transaction for said deposit).

Yes, there are a number of steps to get registered but assuming you have already installed Metamask, and have some ETH at your disposal, then despite the gas costs, there are fewer steps involved than buying a ticket through Eventbrite.

But this is where using Kickback comes into its own, setting it apart from Web2 solutions. At the end of the event, any registered event goers who didn’t turn up, lose their deposit and this pool of money is then returned to all attendees as a … kickback (gedit!). You have the chance to earn for attending an event and however small the amount, it’s a great feeling when you receive that extra nugget of ETH.

Like most of Silicon Valley’s giants, Kickback is capturing value generated by its users’ activities. But instead of keeping those proceeds for themselves, Kickback employs one of blockchain’s USPs — easily distributing value in a one-to-many pattern — to pass those proceeds back to its community of users.

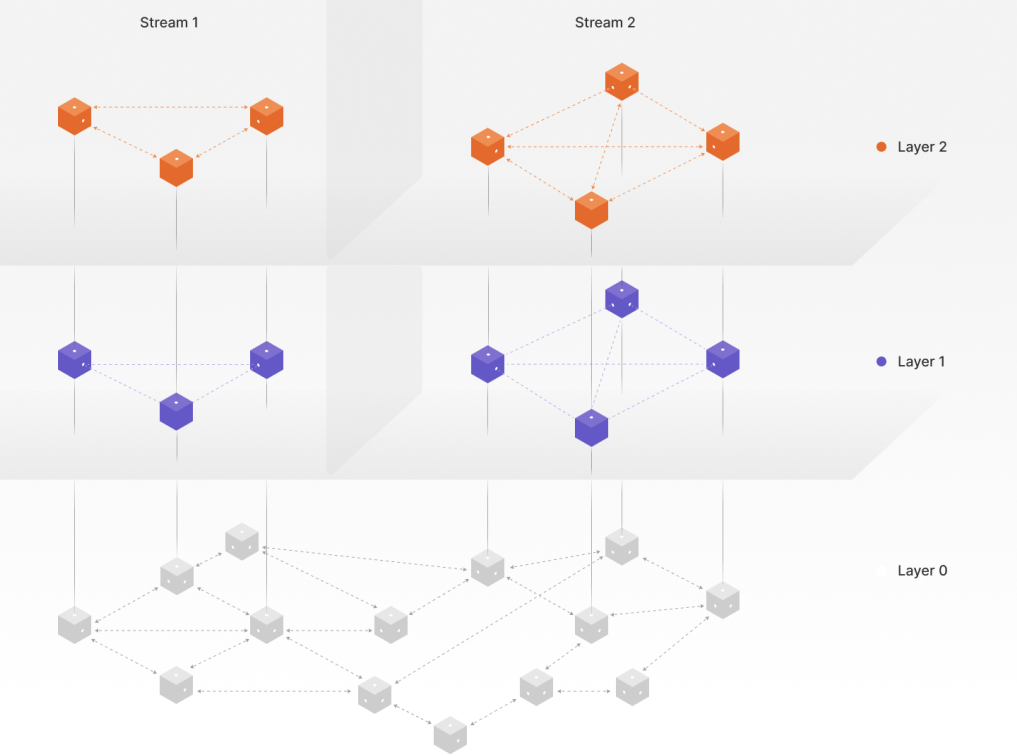

You can imagine this mechanism working for many other types of dApps like say a social messaging platform. Users in that community could permission the data they generate to be sold, and in turn those users would receive the proceeds of the sale of that communally generated data.(Disclosure: this is something that we’re working on at Streamr and we’ll be previewing in Q2 of 2019). Or the gaming industry, where revenues generated for in-app purchases could be re-distributed to the broader community.

In a way, inconveniencing users with such things as gas costs and other infrastructure expenses, which maintain a community’s digital independence, could really help support the same systems that properly remunerate users for their activities. To put it another way, gas costs are the price communities pay to build themselves prosperous digital co-operatives.

The Ethereum space has always attracted those interested in building tools for human coordination (h/t WD). But attracting a new generation of users to Web3 means changing the terms of business. No one wants clunky design and user experiences with seemingly unnecessary friction. But if Web2’s great gambit was to take people’s independence, security and money in exchange for convenience, then maybe Web3 can offer to reverse that flow and give people independence, security and money in return for (a little bit) of inconvenience.