Imagine having a personal diary where you write about your life. Now, imagine owning that diary and not being able to enforce your right to possession. It’s yours, and yet you can’t have it.

How did this happen?

The only Free Cheese is in The Mousetrap

Imagine further that, when you shopped for the notebook, the stationer said you could have it for free. He then mumbled something about the possibility of recording, accessing and using your writing for anything he liked.

Because your persona belongs to the underappreciated world of intangible assets, you couldn’t grasp what was at stake there. Au contraire, the stationer, let’s call him Mark — you know where I am heading with this — eagerly recognised that you had handed him your psychological profile and sentiment live update. You entered a transaction with highly asymmetric possession of information. Now the stationery store is selling copies of your diary to any willing buyer interested in reading it and knowing your inner thoughts, without your knowledge.

Want to read this story later? Save it in Journal.

And for Mark, it’s raining billions.

You, just like me, got grifted by the folks selling free blank canvas for your thoughts, under a “Make the world a better place!” neon-sign. We believed them because they looked so relatable in their shabby sweaters. These are the good guys, we thought, the ones that say: “stay weird,” “do what you love,” and “don’t be evil.” After all, they are not THE BANKERS, those villainous souls living in greed-cladded skyscrapers, relentlessly concocting world domination.

Then came Theranos, Uber’s self-driving cars, WeWork, Cambridge Analytica, the #DeleteFacebook movement, and suddenly we realised that the grass in Start-up Valley was greener only because it had been fertilised with bullshit.

Mark’s Serendipity

We hectically scroll down the privacy policy form and feel relieved at the sight of the accept button. As cookie policies spook the internet, our adaptive unconscious is developing an automatic “Find & Click” response. In a mechanistic manner, we are removing decision points, leaving the cockpit of our digital life in the hands of our automatic behaviour patterns.

Terms and conditions constantly change because the way personal data is being harvested is constantly changing. In 2004, a young man creates a website rating girls by their appearance. Fast forward a few years and he’s holding the greatest heap of personal information ever assembled by humanity. That happened fast, but not overnight.

Most internet services chose to be free to align with the internet value of Universal Access. Asking for money, apart from not being cool, means also fencing people out of your digital backyard. Unfortunately, being cool doesn’t help to keep the light on, and ads started frothing here and there.

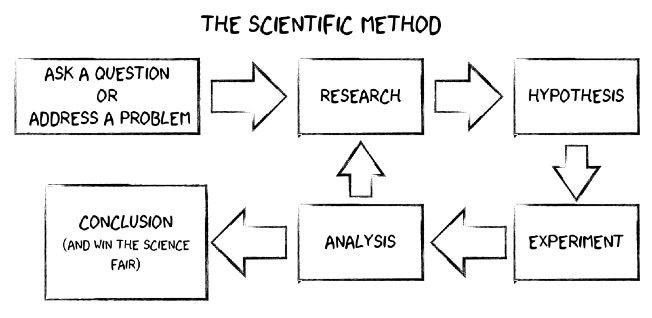

Advertising went from a gut-based discipline to scientific method entailing constant theorising and testing. The goal is no longer to conjecture, while chewing a cigar, what your customer may like. In the brave new world, the objective is to create an ever-increasing framework of understanding around your target audience that helps you reinforce the message in a recursive fashion. For that, you need the help of a sexy woman called A.I. along with her favourite food: data. A lot of it.

The internet is the barn saving algorithms from famine. Everything we do online leaves a trace. The data we produce defines, in part, who we are, what we like, with whom we exchange information, what and who we care about. Aside from Time, Body and Mind, your identity is arguably the most valuable asset you own.

The ruling economic thinking of this age says, in Milton Friedman’s words, that “No-one takes care of somebody else’s property as wisely as he takes care of his own.” Why then, is a society so hot about private property fine with giving away the most personal of properties?

Because we had no choice. Today, the last bastion protecting the exploitation of personal data stands upon the belief that there are no alternatives to centralized data retailing.

We are starting to see some cracks.

Break Free From The Mousetrap and They Will Follow

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) defines the right to Data Portability as:

“the right to receive the personal data provided to a controller […] It also gives the right to request that a controller transmits this data directly to another controller”

Which is Latin for: what you do on social media, what you search on your browser, what you listen to on your phone, essentially all the data you produce using a service or a device, is yours. And just like a paper diary, you can take it wherever you want, even to a marketplace. The question is how to turn a piece of legislation like the GDPR into actionable rights.

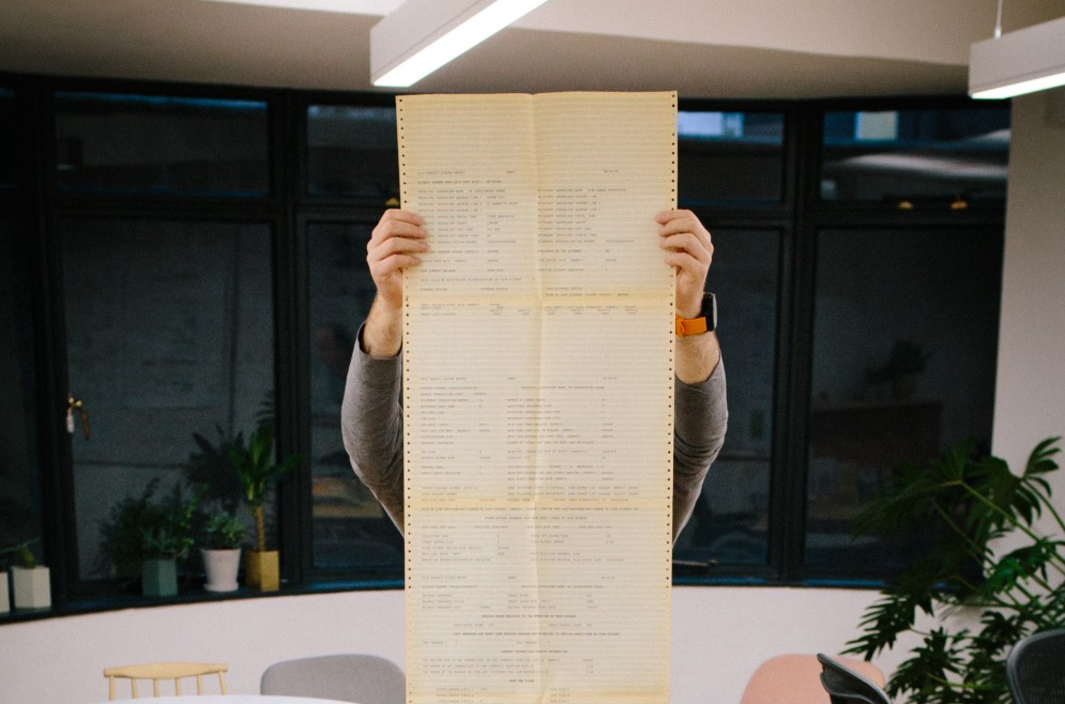

In 2000, Chris Downs collected his on- and offline data and sold it on eBay for £150. It took him a few months and 800 pages to put everything together.

You can see how this is not scalable. Further, on its own, our data does not hold much value, but when combined, it aggregates into an attractive product for buyers to extract insights. This is the idea underpinning Data Unions.

A Data Union is a framework, currently being built by Streamr, that allows people to easily bundle and sell their real-time data and earn revenue.

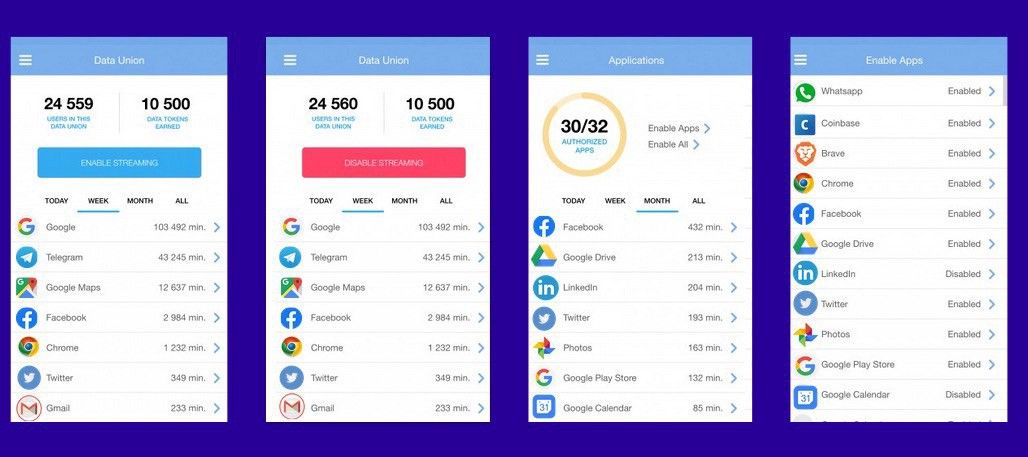

Here’s how it works: a developer creates an application that collects data from a multitude of data producers. What kind of data is open to imagination: Swash collects browser searches, MyDiem gathers phone’s apps usage, Tracey records fishing data.

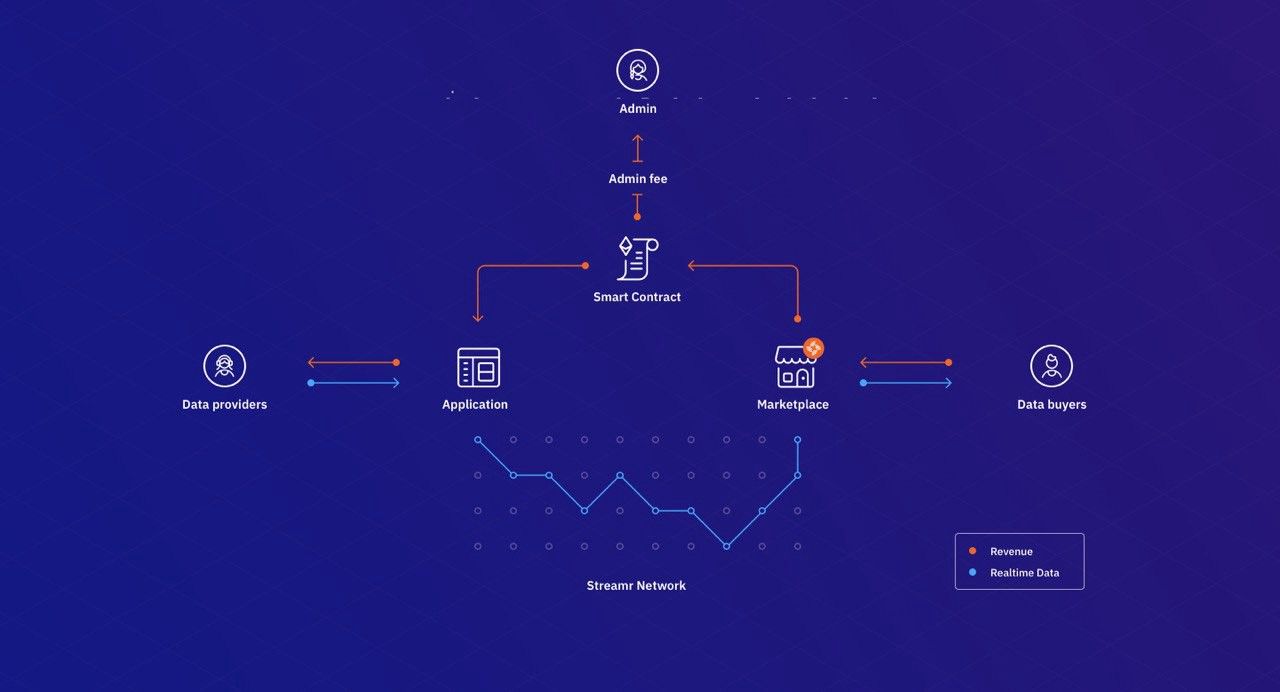

The anonymised data bundle travels on the Streamr decentralized and cryptographically secure p2p Network and gets sold on the Streamr Marketplace. The profits, shy of the developer/admin fee, are distributed among the Data Union participants through a smart contract.

The GDPR and Data Unions give you back choice, control and empowerment, but they are not going to take the Data Cartel out of the picture all at once. Even if you install the Swash plugin, Google will continue to monetise your searches.

Nevertheless, when you decide to own and sell your data, you are remoulding a monopoly into a polyopoly. Which is Greek for a market situation where there are many sellers and many buyers. Competitive forces in this market typology are highly effective in suppressing control centres and providing better transparency and inclusion. According to a paper from the United Nations, “Facebook or Google would lose monopoly powers if the data they collect were available to all interested parties at the same time.”

As long as we are human, we will be vulnerable to persuasion, thus no technology will give us immunity from practices designed to engineer consent. Advertising is not intrinsically evil, yet the Cambridge Analytica scandal showed that there is a veil under which the most treacherous of these practices tend to flourish. The Data Union promises to lift that veil by giving you your share of the profits and by opening the market to a symposium of sellers and buyers, where nobody holds control over the other. If the market stops providing monopolistic benefits, the only way for the data exploiters to survive will be to stop the exploitation and comply with the new rules of inclusion.

The Data Hypenormalisation

In the Soviet Union of the 70s and 80s, everyone witnessed the crumbling of the system, but no one could imagine or dare to propose an alternative to the status quo. Everyone played along, maintaining the pretense of a functioning society. The wintriness of a mock-up system was accepted as the new reality. This effect was termed “Hypernormalisation” by the anthropologist Alexei Yurchak.

In today’s Data Economy we are walking a thin line between a global, secure, accessible, neutral network of information and a dystopia where, without free-floating market prices, a few firms are capturing all surplus values created by data — your data — and they are amassing unprecedented wealth. Today’s Data Economy is not a free market. With few specialised firms anchored to their data-product niche, the system is highly uneven, featuring asymmetric bargaining powers. It is a system designed to benefit the few at the expense of the many.

Ignoring the abuse that is being perpetrated on your digital property is like hurrying down a steep staircase with your hands in your pockets.

You may survive, but you are not going to win a medal for smartest guy in the room.