I’ll start with a personal story. Just over a decade ago, when I was a freelance journalist, three police officers from the Greater Manchester police terrorism unit came knocking at my door. When I asked why they had shown up at my flat, they told me they wanted to talk to me about the book I was in the middle of writing. Not the kind of thing you’d expect to hear in a democracy, where the writing of books should never be the concern of the police.

After I let them in, they served me with a draft order instructing me to give them all of my source materials — recordings, notes, transcripts — pretty much everything I’d created in the course of my reporting of terrorism. Of course, journalists don’t give up their sources. We don’t hand over notes and recordings for fear of betraying those which we have promised confidences to. So I fought it. And a few months later I was sitting before three of the most senior judges in the UK listening to their verdict.

Although the court came to modify the scope of order, in the end they agreed with the Manchester police. And in that moment I came face to face with the realisation that if I didn’t want to do what three judges had ordered me to do — hand my precious belongings and my journalistic integrity to the police — I would likely be put in jail. The period of hearing out rational debate had ended and even though I’d committed no crime, nor caused civil injury, I could be forced against my will to do what the representatives of the state wanted me to do because, simply put, they had the right to put me in prison. I had come up against the wall that is the State Monopoly on Violence. So I gave in.

A few years later, I would come against the Monopoly on Violence again in a more direct fashion after getting whacked over the head with a truncheon by a police officer at a protest over student fees. I was covering the protest as a journalist but I knew there would be little point complaining. In such circumstances, officers are given much more latitude to employ violence lawfully. Privately I joked afterwards that I was grateful that the cops didn’t prosecute me for allowing my head to get in the way of the administration of justice.

States often abuse their Monopoly on Violence with total impunity. A lack of competition will have that effect.

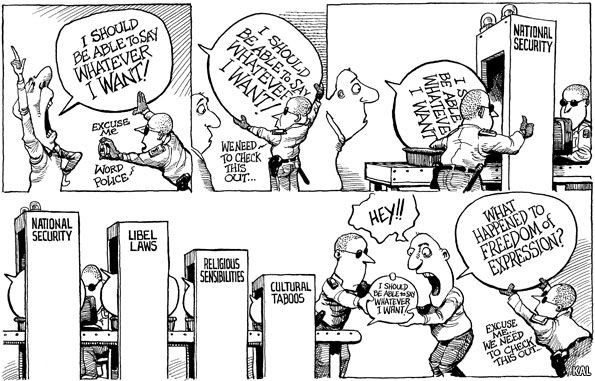

Interestingly enough I’m writing this from a hotel in Istanbul, Turkey, where it turns out, searching for the term “the Monopoly on Violence” on Wikipedia is banned. I only discover this because after trying a few times and receiving an Err_Timed_Out page, the hotel manager suddenly appears at my breakfast table and presents me with a cartoon from the Economist about freedom of speech. “Isn’t this a funny cartoon?”, she says, laughing nervously. I quickly realise what she means and stop what I’m doing so that both she and I don’t get ourselves into serious trouble.

Of course, there are benefits to states having a Monopoly on Violence. Afghanistan and Somalia in the 90s are examples of what happens when there is no such monopoly. Hobbes was right; existence becomes, “nasty, brutish and short”. But in the modern era, the downsides are also very apparent.

The above examples are overt uses of the Monopoly on Violence. But there are many covert uses too. The Spy Cops scandal, where police officers appropriated the IDs of dead babies, and had children with ostensibly non-violent activists to maintain their deep-cover, is the horror version of Joseph Conrad’s, The Secret Agent. Except it was perpetrated by the UK’s largest policing authority, acting within a democracy with supposed civic controls over such matters, in the 21st century, not the 19th. States often abuse their Monopoly on Violence with total impunity. A lack of competition will have that effect.

In short, if you want to achieve serious change and you aren’t willing to be fined, go to jail, be killed, or renegotiate that monopoly through taking up arms yourself, (and how many political movements from the Suffragettes to the US Civil Rights movement, to Indian Independence, to the struggle against Apartheid, have done just this) then you better be prepared to roll over and submit, however good or righteous you think your cause might be.

In Defence of Szabo’s Law

So what has any of the above got to do with Ethereum governance? It’s become a heated topic of late. The tension at ETHCC in Paris at the start of March was palpable. There are flame wars brewing around Parity stuck funds, how to resolve the interests of well-funded incumbents vs new but much poorer entrants, how to push through upgrades, diversity and equal representation, and much more besides. It’s all feeling particularly fractious. Maybe the current very heated atmosphere might die down as crypto winter turns to (literal and figurative) spring. But the underlying issues aren’t going away.

There’s no point attempting to reference everyone here, despite the welter of incredibly well-articulated arguments. Lane Rettig’s opening talk at ETHCC summarised many of these points as did Hudson Jameson’s talk. Most of all, Primavera de Felippi is an especially cogent expert on these matters.

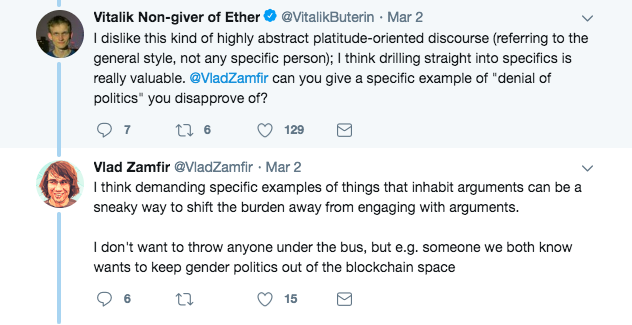

One particular proponent for the pro-governance point of view is Vlad Zamfir. Zamfir believes the reason for our lack of governance is our adherence to what he terms, (Nick) Szabo’s law. Given that blockchains will want to be, and should be legal, Zamfir asserts that we should abandon the mindset that the only acceptable changes to the protocol should be those that “are required for the purpose of technical maintenance”. In effect, we should dump the thought that ‘code is law’ because this a misnomer in actuality, and “Szabo’s law is is too radically anti-legal to be part of a sensible crypto legal system”. It’s simply not tenable, he argues, to tell people there can be no restitution in our system because the code runs autonomously.

Leaving aside the practical difficulties of trying to make a global protocol ‘legal’ in even half-a-dozen jurisdictions, let alone 200, I find Zamfir’s assertion that blockchain should endeavour to be legal for legalities sake, toadying of the worst kind. Ethereum’s vision has always been big and bold enough to set the ethical terms for itself, thereby forcing legal jurisdictions around the globe to follow suit, rather than the other way around. Why change that? Especially when state laws are not built around any consent to be governed, which any self-respecting Etherean would recognise.

More simply, ask yourself this: do we want Ethereum to be “legal” in Iran, Turkey, China or even the USA? Looking at what happened to Google and Facebook when they adopted that outlook might offer some salient lessons.

But the more fundamental point here is that as soon as you demonstrate that you are operating a quasi-judicial system of any kind, you make yourself utterly susceptible to having your quasi-judicial system coming under the larger jurisdiction of a state that views itself as sovereign. You will have identified a locus of power for states and will subsequently be made to stand under them. And there lies the problem. Is any Etherean willing to be heavily fined, or go to prison to keep the Ethereum network online?

And what will happen if Ethereum starts challenging financial structures of say incumbent military-run businesses of say Pakistan, Iran or Egypt, and Ethereans get defined as financial terrorists under the “law” of those countries? Or someone gets bumped off? And please don’t dismiss this as hyperbole. Investigative journalists regularly get killed, in Russia, Latin America even in ‘blockchain friendly’ Malta for god’s sake — for just exposing the fact that illicit financial structures exist, let alone attempting to take them down.

‘Sorry, there’s nothing we can do for you … [because the code runs autonomously]’ is a profoundly powerful response.

And although Ethereum governance may already be something which outside parties believe they can already point to in order to hold named individuals liable in a state court, that in itself is not a de facto reason to strengthen their argument by introducing ever more, and more formal, governance procedures.

So when you take these factors into account, the State’s Monopoly on Violence enforced through overt practises like the courts, and the willingness of even democratic states to engage in deeply anti-civic practises, the response, “Sorry, there’s nothing we can do for you [because the code runs autonomously]” is actually a profoundly powerful one.

Zamfir is right when he says, it just isn’t true that the code runs autonomously. Yes, it is still humans who choose to upgrade the basic protocol. Hell, the computers are still plugged into the walls. And de Filippi identifies lots of other vectors of attack that courts could deploy in this regard. But Szabo’s law is also another way of saying, no particular human is in charge of this revolt carried out by digital means. If we can’t all be as anonymous as Satoshi, then the best we can do is create a round robin of epic proportions. And if you’re not familiar with the original round robin, it is ‘I am Spartacus’ in letter form: a circular protocol ensured a level of anonymity for petition organisers.

We should endeavour, not to be legal, but to be like a force of nature against which the power of states not only fails, but is seen to fail in the most ludicrous fashion. 2,500 years ago Herodotus and his audience laughed as he retold the story of Emperor Xerxes commanding his soldiers whip the waters of the Hellespont for destroying his newly built crossing that would serve as a bridge to invade Greece.

Ethereum should for as long as possible endeavour to operate, and be seen to operate like nature — outside of human control. And when kings and courts try to whip us, let them look ludicrous for even trying.

Thanks to Juuso, Francine, Wei, Melchior, Maria and others for all their help with this.