Table of Contents

Do people care about privacy?

In May 2012, I made national news in the UK. In protest over Facebook’s $100bn IPO, I deleted my account, and this was a sufficient offence to warrant being hauled into a TV studio. When asked to explain myself, I replied: “I didn’t want to be an infoslave any more.” Facebook, I argued, had turned us all into data production factories. Enough was enough. “To see, in a sense, this $100bn dollar value created out of people’s shared dreams and hopes and discussions and pictures — that seems to be a step too far. I don’t want to make Mark Zuckerberg any richer.”

Motivated by disgust, I’d gone out on a limb. The newsreader’s retort was blunt: “This is an argument you’ve already lost. Hundreds of millions of people have bought into Facebook.”

He was right. The network effects of Facebook had trammelled any socioeconomic argument that I or others could put forward. No one seemed to care about privacy. Or equality. Or even their own dignity.

Three years later in late 2015, my then colleague at the Guardian, a junior reporter named Harry Davies, uncovered what would become known as the Cambridge Analytica scandal. He asked me to give him a hand in getting the desk editors more interested. I said I’d try to get a quote or two from respectable US commentators to lift the story’s prominence. I rang David Frum, George W Bush’s former speechwriter and Atlantic senior editor. Frum’s response was similarly blunt. Americans don’t care about online privacy. He didn’t see the interest. I took it as a sign that nothing had changed since 2012.

I was reminded of these two experiences once again whilst sitting in a research project I’d helped set up a few months back. Asked about their attitudes to privacy and data monetisation (how comfortable people feel selling the data they produce whenever they use digital platforms) a single response was stark in its repetition. To quote a respondent directly: “We use the internet, they [the tech companies] gather our data. That’s just the kind of give and take [we’re involved in]. I’m not hugely fussed about it.”

How have attitudes shifted so little in the last decade, despite the horror stories which continue to pile up? Cambridge Analytica may have pierced through into the general consciousness, but that story is one amongst what must be scores of major data scandals every year. What about the anti-virus software that itself acts as spyware, hoovering up your most intimate data to retail to the world’s biggest corporations? And speaking of hoovering, what about the vacuum cleaners that send your home’s floor plans to China? Or the computer fonts that log your every word? And this is only what is happening today. If you really want the willies, it’s worth listening to the ever erudite Jamie Bartlett on what might happen in the near future. [See 25:38]

People are not oblivious to the reality of the situation. Far from it. They do, on the other hand, feel dislocated from and disempowered by the tech they use every day.

For those who believe in progress, these sentiments are dispiriting. Not only have people realised they must live under the tyranny of terms of conditions, they feel they have no choice but to abide by it. They’re trapped. So who will stand up for their rights?

The answer to this would normally be government. But governments are in on the act. They are busily collecting and even overtly selling our data. Whether it is the DMV hawking driver information, the NHS selling patient info to Google or, as Edward Snowden revealed, institutions like GCHQ or the NSA forcibly contracting the very same tech companies they should be regulating to do their data collection for them, the examples are plentiful and egregious.

But here’s something else I found in that research: if you stick with people just that little bit longer, it turns out they really do care about their privacy, and they do want some control over the information they create. The response “I don’t care” is often a shield, a defence mechanism against the sense of helplessness at the sheer scale of the problem. But that shield is protecting something precious that lies just beneath: hope.

Hope in the Dark

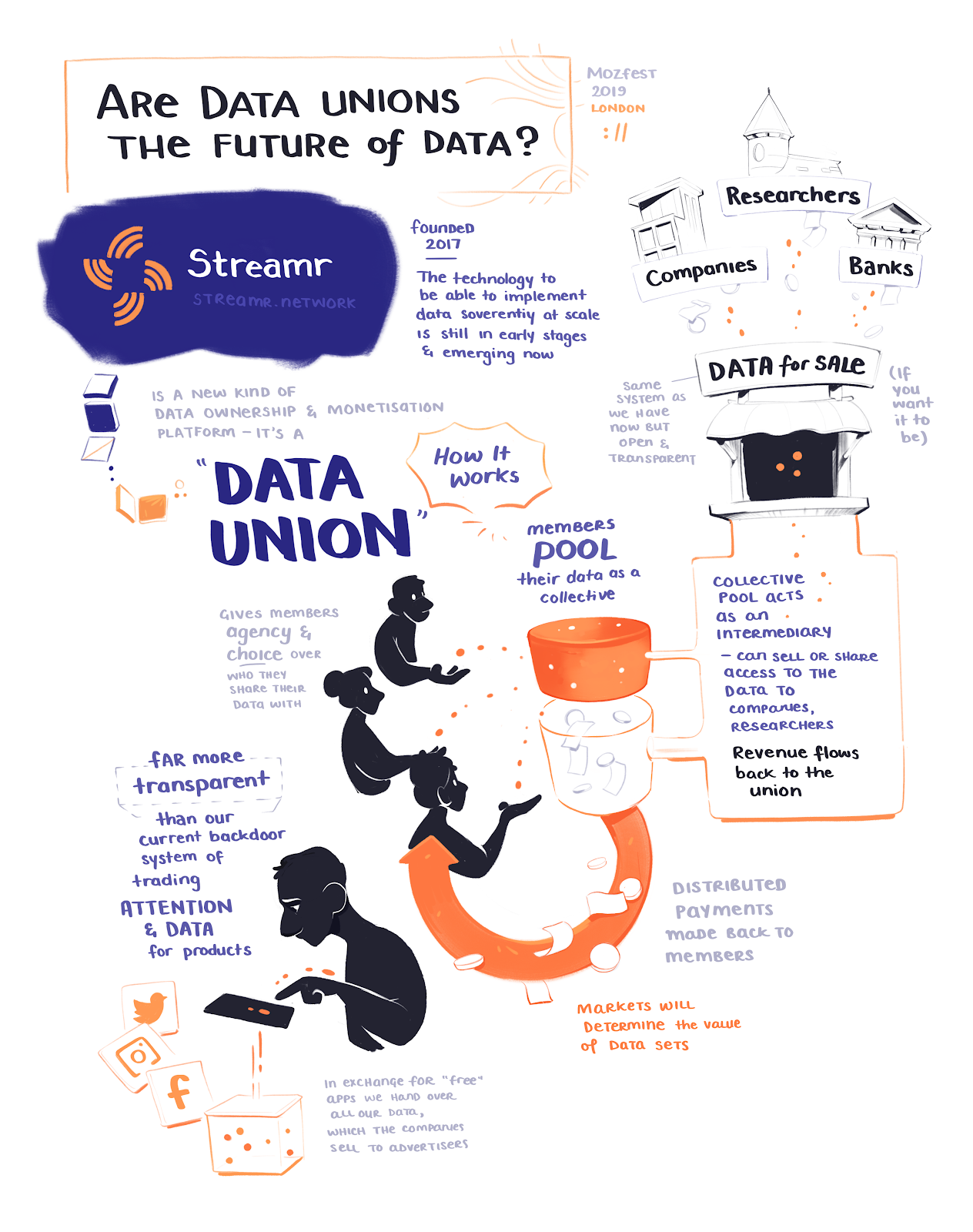

The research was commissioned by the open-source technology project Streamr. I began working for Streamr three years ago because I was drawn to its mission to change the landscape of personal data.

There’s a summary of the research findings here, but, for me, the most interesting discovery, not enumerated in the summary, was that when respondents tell you that they don’t care — about data, about privacy — that’s far from the full story.

Consumers today are cornered. “We don’t have much choice,” said another respondent, “we are signing our life away.” When faced with the flagrant and seemingly unstoppable use and abuse of their digital identities, and the sense of powerlessness that accompanies it, people default to telling themselves they don’t care. It’s easier that way.

The truth of this hit home most clearly when we gave our attendees just a modicum of control over the data they create.

When asked if people would be interested in selling their data as part of an online collective or, as we’ve termed it at Streamr, a Data Union, an outright majority of participants scored the idea highly. When we gave them a working example of a Data Union (Swash, a browser plugin) to play around with, they loved the Data Union concept even more.

When people realised they could have a say over who they shared their data with, where it was sold, what price it could fetch, they became increasingly animated.

In part, Swash acts as a basic enough tool to allow people to have a genuine say over what data from their browser they’d like to share (and monetise) and what they would prefer to remain private. It turns out that, given the chance at reclaiming some of their power or imagining an alternative to data tyranny, consumer indifference fades away.

When given a real choice, our participants underwent a remarkable transformation. When people realised they could have a say over who they shared their data with, where it was sold, what price it could fetch, they became increasingly animated. They engaged and were thoughtful about their choices. If anything, the researchers were soon trying to manage over-expectations — participants suddenly wanted full control over all the data they generated on every platform they visited. The mental shackles of ‘infoslavery’ were off.

How do you reform the data economy?

In the midst of our slow-burn techlash, the world isn’t without alternative visions for a data economy. Given that we currently inhabit a Panopticon hell, imagining better could perhaps be deemed an easy feat.

Those visions (oversimplified here) can be described like this:

- Open data — A world in which vital and useful data is shared between all parties and made open for anyone to utilise, rather like a commons.

- Privacy First — digital platforms should minimise the data created about users and personal data should remain private and under individual control by default. Sharing data should happen only in the most necessary circumstances and everything should be encrypted.

- Data ownership — People should be able to take control of the data they generate through the framework of ownership and it should be within their right to license the use of that data to whomever they choose.

If you can’t put your ideas into practice, then history eventually renders them worthless. By that metric, the first two visions have had significant successes.

The open data movement has by-and-large been championed by Tim Berners-Lee’s think tank the Open Data Institute. It has delivered the open banking movement in the UK and also helped to establish a norm that data produced by democratic governments should be open for anyone to utilise, for free.

The Privacy First movement has arguably had even greater success. A good number of organisations, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Privacy International promote pro-privacy aims, and the principles they espouse have informed powerful pieces of legislation like GDPR and the newly enacted California Consumer Privacy Act. Most importantly, there are now a huge number of pro-privacy tools that people can use. Tech like Whisper, Signal, WhatsApp, Brave, DuckDuckGo and Firefox have meant that explicitly pro-privacy software has been put into the hands of tens of millions of people.

And yet, although the open data and privacy visions have won scores of battles, they have failed to win the war. On a global scale, there is less privacy and more data siloed away than at any time in history.

Perhaps with the Open Data movement the problem is this: the Open Data movement demands that the state enact laws mandating the data behemoths give up what they regard as their private property and share it with the rest of us.

The tactic here is to extrapolate power to the smallest number of people (legislators) in the hope that they will stop another tiny number of very powerful people (tech oligarchs) from staying rich. Even if such a monumental lobbying effort should succeed and open data laws were to be enacted, its success would be momentary. How long would it really take Big Tech to counter-lobby those Open Data provisions? It’s such a flawed tactic that even Berners-Lee is pursuing another way forward.

Conversely, Privacy First’s great tactical gambit is to rely on others, billions of others, adopting and internalising its high, almost Puritan ideals. These privacy warriors have set sail in the digital version of the Mayflower to remake the world anew, insisting on an attitude to privacy so universally reverent that everything, from the phone in your hand to your coffee maker to your car, will be technologically imbued with a deep sense of respect for the individual. All information points must undergo a complex moral test before being released: does the publication of this data point threaten my moral right to shape my own identity?

And here the problems with this strategic approach multiply. Firstly, how far can you culturally tip people toward putting privacy above convenience? The results speak for themselves. The cognitive overload of regularly asking those ethical questions, and constantly adopting and maintaining privacy-enabling technology, stands no chance against the temptation of convenience, as evidenced by how much people are paying Jeff Bezos to spy on them through Alexa. Consumers put convenience above privacy billions of times each day. The results-to-date say the fight for minds isn’t winnable.

Secondly, the privacy Puritans simply do not have the resources to make the world of both software and hardware anew. Whether they know it or not (and many of them know it), what they are really calling for is a remaking of any item of capital with a circuit board. To ensure that there are no leaks of information of any kind that might once again empower the centralized conglomerate, every single gadget in the world will need to be remade. When 99.99% of hardware makers, from cars to phones to watches, have alternatively aligned interests, this simply isn’t feasible. And if you can’t remake all the hardware of the world (you can’t), then privacy Puritans are left trying to persuade the Apples and Fords and Facebooks of the globe to ensure our privacy for us. That’s a pretty weak position.

This turns us to the third issue, which is that whilst humans can be abstracted to the model of a privacy-loving individual, actual humans, the real ones who breathe and work and consume, are simply not private. People want and need to be connected. As the entrepreneur and recent NYC Democratic congressional contender James Felton Keith recently put it to me: “We thrive as a species because we’re interconnected”.

If The Virus has taught us anything, it is just this lesson: our interconnectedness is a vital and fundamental part of modernity and of our humanity. As my colleague Faris Oweis warns, COVID-19 is testing that line between our privacy and our survival as an interconnected species.

Countries are deploying surveillance tech and gathering our location and health data to mitigate the spread of the virus and ultimately the death count. Are we willing to provide this data to these stakeholders in return for the potential to flatten the curve? If so, are we then also fine with health agencies or insurance companies capturing our data to monetise it? Before you say no, what if that information is sold to pharmaceutical companies, who then create a vaccine based on the information?

Privacy systems designers rarely take that need for interconnectedness fully into account. In a data economy context, the right to privacy gives you the right to say no; to assert that you will not share information about who you are and what you do. But we also live in a world where we want to say yes. Pro-privacy systems rarely facilitate that desire.

Whilst the ideals and aims of the privacy and open data movements are in so many ways well-intentioned and correct, the results demonstrate that the strategy and tactics have failed. Despite a decade or more of pro-privacy and open data initiatives, the vast bulk of humanity is worse off in terms of both open data and privacy than in any other time in human history.

So let’s just say it: the privacy and open data movements are dead. Let’s give them the funeral they deserve, but let’s bury them deep in the ground.

Long live data ownership

So what about data ownership, the third child in the line of a potential succession of Utopian ideals? The idea has been backed by an eclectic but largely uncoordinated bunch of radical thinkers, from Jaron Lanier and Yuval Noah Harari, to Will.i.am. Recently, the better coordinated MyData movement has filled many gaps, but actual implementations have been very thin on the ground, and past emanations of the idea have floundered. Other startups who’ve stepped into the space seem to skirt around giving consumers genuine ownership of their data — instead they offer cash in return for things like consumer surveys, rewarding consumers for providing even more data, not for the data they have already created.

What has bedevilled this vision of ownership is that enabling individuals to own and trade their data is a huge technical problem. To make the point, let’s briefly recall one of the first experiments in self-monetising personal data. Two decades ago, a British man named Chris Downs decided to try and sell his data. He downloaded his personal information from various companies and websites and put it up on Ebay for auction. Ultimately, someone paid him $315 in today’s prices. Not bad, but not exactly scalable.

From a technological infrastructure perspective, individuals who try to own and trade their personal data today are still lumbered with the same ineffective tools. As Downs put it in his wonderful 2017 piece re-remembering his experiment: “Disappointingly, nothing much else has changed. The experience [of selling your data] is just as clumsy, frustrating and disorganised as it was 17 years ago”.

The experience [of selling your data] is just as clumsy, frustrating and disorganised as it was 17 years ago.”

For those who believe in the ownership model for data, this is a disaster. The infrastructure and institutions simply aren’t there. And as the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto showed, without infrastructure and institutions to make ownership rights realisable, not only do you not have rights, you don’t have a proper economy either. Imagine trying to claim title to a house without estate agents, lawyers, surveyors, monetary systems, legal systems or a title registry. Impossible, right? This is where we’ve been with data ownership.

I would argue that it is just this lack of infrastructure for realising ownership, not privacy rights, that has left people’s data open to abuse all these years. The perfect example is Facebook itself. They proudly declare: “You own the information you share on Facebook”. But there’s no way to utilise or instantiate your property rights. It’s all empty. Because they have the means to monetise the underlying asset and you don’t, you are weak, and they are strong.

As Montana Senator, Jon Tester, quipped to Mark Zuckerberg in a 2018 congressional hearing, “You’re making about forty billion bucks a year, and I’m not making any money — it feels as if you own the data”.

Roads and rails for the people

Given that the personal data market is worth hundreds of billions of dollars, why aren’t there better solutions for the millions of potential Chris Downs out there? We have apps for all sorts of services — why not apps that help you monetise your data?

The answer is that genuine individual data monetisation is technically very difficult to achieve. And until now, few of the parts of the puzzle have been in place to operate it. (Just a caveat here. What we’re talking about is the infrastructure to deliver real-time data. Static data delivery is somewhat easier to build, but real-time is where the future value of any data system will be situated). The main issues are these:

Transporting data

If you’re going to sell your data to someone else, you’re going to need a way to move it from its original source to a prospective buyer. Downs used the post to send his 800 printed pages. Today, an individual could use Google Drive but this is horribly inefficient at scale. Big tech companies have built a data transportation backend for themselves, but it’s been out of the technical reach of ordinary individuals to exploit that type of infrastructure with any sort of ease.

Data discovery

Again, like Downs, sellers and buyers need a place to discover data and eBay itself won’t scale to this purpose. You need specific data marketplaces that actually point buyers to what they want. But there’s a second part to this: aggregation. Data buyers aren’t going to negotiate the purchase of data from thousands of Chris Downses. It isn’t practical. Individuals need a way to aggregate or pool their data into one, clean, simple-to-buy data product on a marketplace.

Micro-payments

Just when you think you might be able to solve the latter problems, along comes the killer blow. People need to get paid. No problem, right? We have banks and money. But if a buyer spends $10,000 on a data product, which is drawing data from one million people, how do you send them all one cent each? Regular banks aren’t going to be able to do this. You need a micropayment service.

If you want data ownership to become an infrastructural reality, then data transport, a marketplace and a micropayment service are your basic technical requirements.

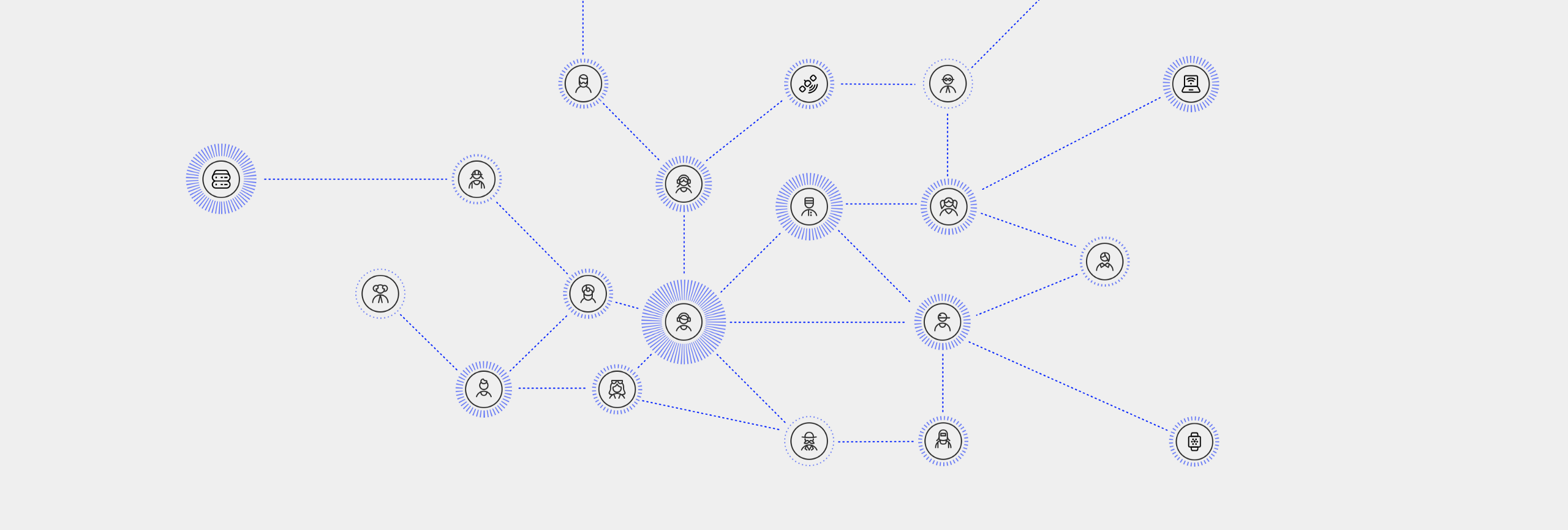

Remarkably, the Streamr team is seated squarely at this conjunction of real-time data and digital payments. By October 2019, they had not only built the start of a decentralized, permissionless, end-to-end encrypted Network for data transport but also a data Marketplace for the discovery and purchase of data. A micropayment service exploiting cryptographic tokens, which they called Monoplasma, was added to the mix, which meant that all these parts — a data network, a marketplace and micropayments — could come together in Streamr’s Data Union developer framework. This will be released later this year.

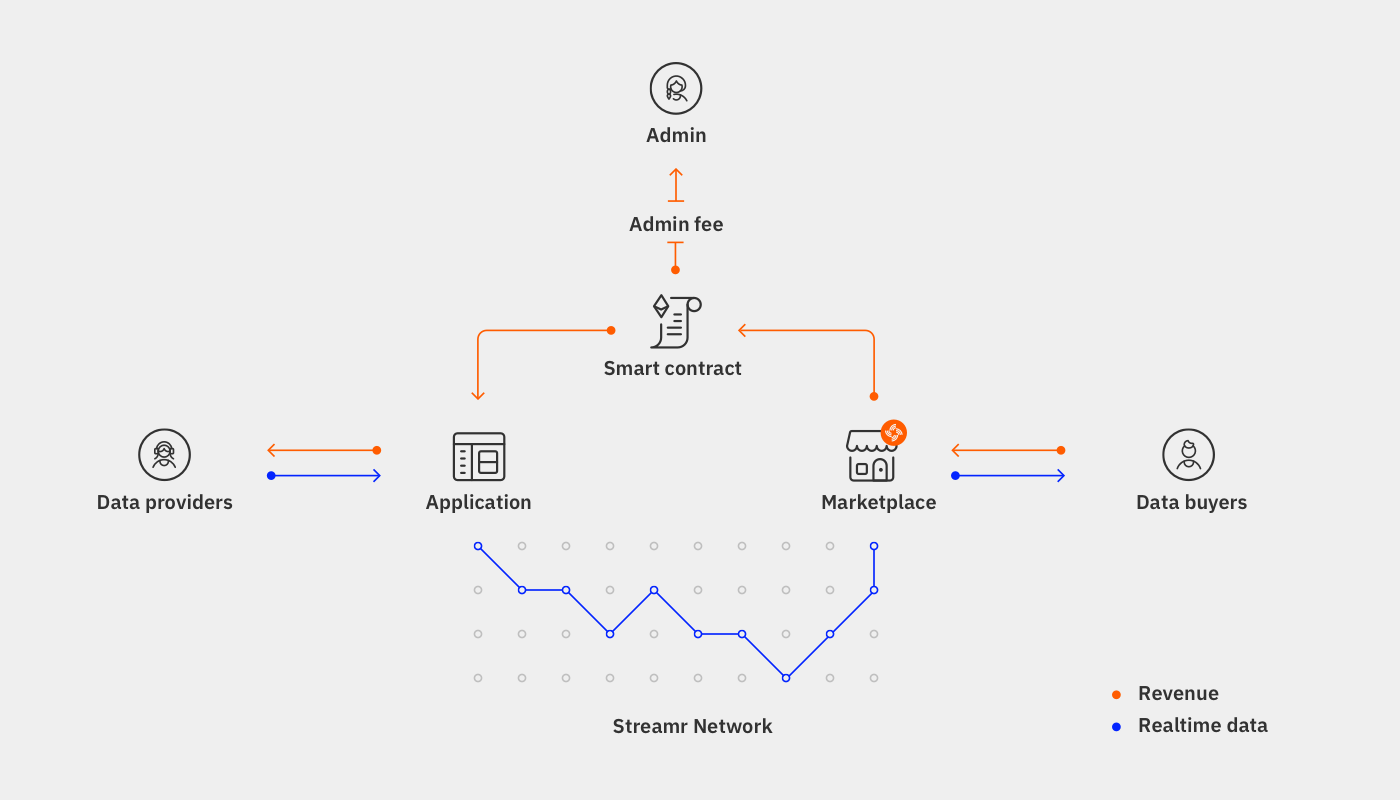

Here’s a technical outline of what’s going on:

How the tech is built is of paramount importance. Usually, a company will sit in the middle of these transactions. That way they always call the shots. But in Streamr’s ecosystem, the data and the payments travel directly between individuals and buyers (peer-to-peer), and through two separate decentralized networks. This allows, crucially, for genuine consent. If I as an individual do not want to share my data, there is no centralized party who can override my wishes. In other words, no means no. But yes, really also means yes. And here you have all the tools at your disposal to action that choice.

I don’t want to shill here, but for the sake of this essay I do want to elucidate what an actual Data Union looks and feels like. Again, ideas are a dime a dozen. Actual implementations in the personal data monetisation space are few and far between. A practical working example of a personal data monetisation tool is Swash. Built by a small team based out of Turkey, Swash is the world’s first Data Union built on top of the Streamr stack. Here’s what the search data of its 1000 members looks like:

I love this GIF because here you can literally see over 1000 people coming together and acting collectively.

For clarity, Swash makes money, too. And they should. The team built the app, continue to find buyers for the data, manage legal contracts, refine the data and bring in more Data Union members. That’s a lot of work that no one is going to do solely out of the goodness of their heart. But their reward is limited. When the data sells, Swash can take a maximum of 30% of all revenue.

Streamr has built a generic framework so that anyone can build a Data Union like Swash for themselves. The system is permissionless and, most importantly, open source, which means any dev team with the right skill set can come along and start creating a Data Union.

Of course, Streamr’s technical stack is not the only toolset that directly allows people to make data ownership a realisable right. There are others including teams in the MyData consortium who are very much doing just this. The EU and others have also started funding the development of data portability and personal data monetisation projects. But to my mind Streamr has set the working standard which I’ve not yet seen replicated anywhere else.

Data ownership: a socioeconomic revolution?

Now that it’s possible to overcome these technical hurdles, let’s try and figure out what the benefits of data ownership through these Data Union (or data cooperative) set-ups might be.

Let’s start by saying that, in one sense, these Data Union structures aren’t particularly radical. To quote Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl, one the central progenitors of the data cooperative idea (they term it a Mediator of Individual Data or MID):

“Entities of their shape and necessity in the physical world could hardly be more familiar. Organizations like corporations, labor and consumer unions, farmers’ cooperatives, universities, mutual funds, insurance pools, guilds, partnerships, publishers, professional societies, and even sports teams are all critical to dignified societies and effectively serve the MID function.”

It turns out healthy modern economies are full of agents and institutions who represent our interests. The only novelty with Data Unions is that they act for us in the digital realm.

Let me also define the type of ownership. Often when people consider data ownership, they think of it in the simplest terms. I own this lumber. I sell it to you. You now own it and I have no claim. But property transfers encompass a far broader spectrum of behaviours.

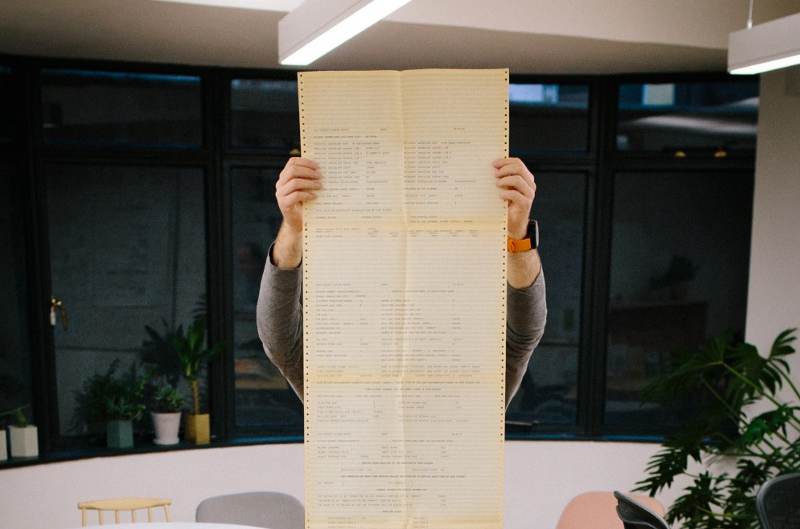

Because of the richness of what data represents, when transferring data as property, data cooperative style organisations will likely adopt leasing rights more akin to authorship rights than simplistic property rights. The economist Maria Savona, has laid this out really well. And if you’ve ever seen an actual data sales contract, the lease framework is not far off how they are already framed. Companies don’t just sell their data, they grant access rights to it with complex clauses. Those contracts sometimes run into over a hundred pages.

So with those caveats declared, let’s look at the specific benefits of data ownership.

Far better enforcement

Those who battle for privacy tend to leverage a legal framework that has only really been formed in the last 70 years or so. In Europe, the right to privacy was developed as part of the European Convention on Human Rights. What almost always seems to be forgotten is that, at least in English common law, privacy is far more deeply rooted in property rights than within our modern human rights framing.

The classic common law case, which influenced the drafting of the US 4th Amendment, is Entick V Carrington. Entick was an 18th-century London-based publisher, and King George III’s Minister of State didn’t like what he was writing. So the minister sent his heavies to break into Entick’s property, search for and confiscate his pamphlets. Entick sued. Not for a right to free speech or privacy, but for trespass — an offence of property. The judges were clear: Entick had a right to enjoy his property without lawful intrusion. As the Chief Justice declared in his 1765 judgment:

The great end, for which men entered into society was to secure their property. That right is preserved sacred and incommunicable in all instances, where it has not been taken away or abridged by some public law for the good of the whole.

I own these papers, you cannot have them. I own this house, you cannot come in. I own this land, you must not intrude on it. For hundreds of years, property-based rights have given people far more privacy against the powerful in a way that the modern right to privacy cannot rival. One day soon we should be able to add this to the above declarations: I own this data, you cannot take it.

So if you want privacy from Silicon Valley and nation states, property rights represent a much stronger set of rights than modern privacy rights. But there’s a second point here. Rights without any possibility of enforcement are fairly useless rights. Currently, government agencies or companies are in charge of enforcing an individual’s right to data privacy. We all know this isn’t working. Government agencies are hopelessly outgunned in both the scale of the problem and the strength of the powers they are up against.

But when data is treated as property in free exchange, as opposed to being reduced to a moral question around the release of information, suddenly the enforcement possibilities increase. Data Union members don’t have to be rich or highly educated to protect their privacy. Now they’ll have an organisation with a financial incentive to work on their behalf to enforce their rights.

If a member doesn’t want company ‘X’ to sell their data (because their Data Union is now doing it for them and giving them the lion’s share of those sales), then that Data Union is likely to chase company ‘X’ up and sue it for infringement of what are now commercial rather than simply human rights. Why? Because they get paid for enforcing their users’ rights. And so does the Data Union member.

De-monopolising data sets

It is perennially fascinating to me that one of the main properties of digital information is that it is entirely replicable at the push of the button, and yet somehow a handful of companies have gotten incredibly wealthy by managing to retain their monopoly over it. This is of course partly based on their ability to use property rights to enforce their claims to that user-generated information. But that information also resides with the user. If I watch Tiger King on Netflix, Netflix knows exactly what I do and exactly how I watch that programme. But so do I. I just don’t have very good methods for collecting the data and then making use of it.

Now that incentivising the collection and aggregation of that data from the user’s end is a possibility, expect very soon to see the de-monopolisation of data.

A prime example is Google Maps. They control the map app game because breaking in now requires having tens of millions of users to compete with the richness of information that Google’s users supply to Google. No one wants to use an app that can’t tell you how long the journey time is between one place and another. But the app interface and the underlying data powering that app are two separate things. If I can aggregate that location data that Google Maps depends on to maintain its monopoly, my Data Union can then lease that to any app builder who wants to create a new map app. And they can stick any number of new features on it. And that’s just one example. What about doing that with Uber? Or Netflix? Or Amazon Kindles? By creating user-owned data sets outside the control of major tech firms, you are going to increase innovation massively. Revised EU data portability rules, which are likely to drop in the next few years, will only speed up this process.

Data Dignity

Perhaps the last but most obvious thing to note is that users who have been exploited for over two decades will finally have what Lanier and Weyl term, “data dignity.”

Though the data aspect of the phrase is well-defined in their seminal essay on the topic, I’ve realised they don’t actually define what they mean by dignity. I’ll take a stab at it here, and perhaps this everyday example might point towards an intuitive sense of what is meant.

Pretty much every time I land on a website or use an app, I have a 40-page contract of adhesion shoved in my face. These organisations know I cannot possibly read these contracts. They also know I don’t have a team of lawyers to argue the revision of terms, even if I did read them. But they do it so that they can cover their abuses or screw-ups with one tick of a box. I work hard. I keep a good home. I am a good father and friend. I take pride in these things. But every day Silicon Valley treats me like dirt. And for one reason alone. In this situation, I have no power.

To dignify me (and every other person who uses the internet) would mean companies and site owners recognising my inherent position of weakness and nevertheless respecting my choices and concerns. I want to genuinely be able to choose what someone on the other side of that digital interface knows about me, and what they subsequently do with that data. The state and its privacy statutes have not enabled that for me. Under GDPR I am still regarded as a “data subject”.

Legal entitlement to my property will give me back my dignity. Receiving payment for the use of that property gives me back my dignity. Protection by personal enforcement agents gives me back dignity. Having a genuine choice gives me back dignity — I’m being offered something that I can choose to accept or reject. The power dynamics between me and the Valley will be changed, and I will have far more control. As Lanier says, “That’s the way you make a humane culture”.

Conclusion

As if this blog wasn’t too long, I’ve yet to tackle any of the well-observed critiques that people often make about the data ownership framework. I will do that in a second blog, which will be published soon. But to conclude let me say this: we’ve got a long way to go with trialling data ownership as a means of taking back privacy and regaining a modicum of dignity and equality in the process. Mistakes will be made. The tech might be buggy at first. Supportive legislation will be slow in the making. But the longest distance to travel in all of this will be the one we travel in our minds.

I believe data ownership is a great meme, one that will permeate far better than the ideas of open data or even privacy. But shifting internal paradigms — so that people realise they are in control — will still be a challenge. The mental process of emancipation from this state of personal data exploitation will be a long one, requiring patience and guidance. But given our current relationship between the data behemoths and ordinary people, it’s a journey that I’m sure hundreds of millions will be willing to take.

Part two of this essay — You can’t sell your kidneys! Responding to Objections around data ownership — is now published here.